A recent dispute between Gensol Electric Vehicles Pvt. Ltd. (‘Gensol’) and Mahindra Last Mile Mobility Ltd. (‘Mahindra’) over the trademarks ‘EZIO’ and ‘eZEO’ highlights the importance of the test of passing off, brand identity, first in the market advantage and weight of established reputation.

The Single Judge of the Delhi High Court on 13 January 2025, rejected Gensol’s claims of trademark infringement and refused their plea seeking to restrain Mahindra from selling its Electric Vehicle under the trademark ‘eZEO’.

Plaintiff and defendant’s case at a glance:

Plaintiff’s case

The Plaintiff, Gensol Electric Vehicles Pvt. Ltd., is a subsidiary of Gensol Engineering Limited and is a company incorporated in the year 2022. The Plaintiff aspires to accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles for a sustainable future and produces various types of electric vehicles including mobility fleets, cargo vehicles, personal mobility solutions, etc., to cater to varied urban mobility needs.

Around August 2022, the Plaintiff envisaged the development of an innovative electric vehicle that specifically caters to urban mobility. The Plaintiff’s design team incepted the work and on the finalization of the designs, the mark ‘EZIO’ was coined and adopted for the vehicle. Moreover, with the assistance of the third party, the Plaintiff also created the logo, ‘ ’.

’.

Subsequently, the Plaintiff applied for the registration of word mark, ‘EZIO’ in Class 12 on ‘proposed to be used’ basis on 30 June 2023. The Trade Marks Registry granted registration to the said mark on 19 May 2024. The said registration stands valid, subsiting and renewed till 30 June 2033.

The Plaintiff tested its first electric vehicle on the roads of Pune, Maharashtra, on 7 January 2024, after procuring requisite permissions from the Automotive Research Association of India (‘ARAI’) and design registration for its vehicle.

The Plaintiff came across a newspaper article (dated 9 September 2024) that featured the Defendant’ announcement of the launch of its new commercial electric four- wheeler bearing the mark, ‘eZEO’ / ‘ ’ on 18 September 2024.

’ on 18 September 2024.

On further perusal, the Plaintiff found that the Defendant announced the launch of its Electric Vehicle bearing the mark, ‘eZEO’ on its website on 3 October 2024. Following that, the Plaintiff came across the Defendant’s trademark filings for the marks, ‘ZEO’ and ‘eZEO' in Class 12, on ‘proposed to be used’ basis, on 29 August 2024 and 10 September 2024, respectively.

This led to the dispute that resulted in the current ruling.

Contentions of the defendant

The Defendant, Mahindra Last Mile Mobility Limited, is a subsidiary of Mahindra and Mahindra and is a public limited company that manufactures and sells vehicles. The Defendant has been in the market since the last 20 years through its parent company and at present holds 50% of the commercial electric vehicle market share.

Around April 2024, the Defendant envisaged the launch of a new commercial electric four-wheeler with high voltage architecture to amplify its efforts in electrifying last-mile transportation. Amid the development phase, the Defendant bona fidely coined and adopted the marks, ‘ZEO’/ ‘eZEO', being the acronym for ‘Zero Emission Option’, for the said vehicle. The Defendant claimed that the afore-mentioned marks were adopted after conducting a trademark search on the Trade Marks Registry website in April 2024, and market searches, that did not reveal any conflicting marks in the electric vehicle sector.

The Defendant also asserted that along with the mark, ‘Ezeo’, they also use the house mark, ‘Mahindra/  ’ belonging to its parent company to indicate the source of its vehicles.

’ belonging to its parent company to indicate the source of its vehicles.

The Defendant announced the launch of its new commercial electric four- wheeler bearing the trademarks ‘eZEO’/ ‘ZEO’ on the World Electric Day i.e., on 9 September 2024, through press release and promotions on social media accounts, which was subsequently reported by the leading business newspapers.

The Defendant claimed to be the prior user of the mark, ‘eZEO’, given that the use of the said mark commenced on 9 September 2024, whereas on the other hand, the Defendant alleged that the Plaintiff did not even launch its vehicle in the market. The Defendant claimed to be the ‘first in the market’ with respect to its trademarks.

The Defendant highlighted that the Plaintiff first disclosed its mark publicly a day before the institution of the present suit i.e., on 25 September 2024, and has not disclosed the date of launch of its vehicles in the market, owing to the fact that the same is still in prototyping stage.

The Defendant claimed significant dissimilarity with the Plaintiff’ vehicle in design, functionality and target audience. The Defendant argued that the Plaintiff’ use is intended for a two door, three-wheeler electric passenger vehicle, whereas on the other hand, the Defendant’ trademark is a four- wheeler electric commercial vehicle catering to dissimilar purposes and consumers. Given the same, the Defendant asserted that there was no possibility of confusion among consumer, traders, or the public.

Notwithstanding the same, given the present conflict, the Defendant proposed to use only the trademark, ‘ZEO’, without the letter ‘e’ and additionally add the house mark ‘MAHINDRA’ in respect of its vehicles.

Analysis and decision

The Court called upon the parties to explore the possibility of settling the matter. At the hearing the Defendant proposed to modify its mark to ‘ ’, however, the same was not amenable to the Plaintiff.

’, however, the same was not amenable to the Plaintiff.

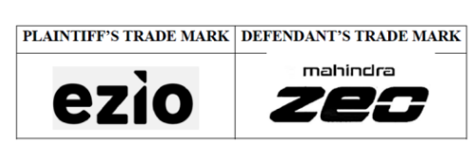

The Court pronounced that the Defendant shall use the modified mark, ‘ ’ and not ‘eZEO’. The Court compared the Plaintiff’ mark, ‘

’ and not ‘eZEO’. The Court compared the Plaintiff’ mark, ‘ ’ with the Defendant' mark, as illustrated below:

’ with the Defendant' mark, as illustrated below:

and observed that the Defendant dropped the letter, ‘e’ and added its house mark ‘MAHINDRA’ in the revised mark. The Court further noted that the earlier mark of the Defendant ‘eZEO’ was almost identical to the Plaintiff’ registered mark ‘EZIO’, however, after the modifications made by the Defendant, the two marks cannot be said to be identical. The Court stated that it would have to examine whether or not the modified mark of the Defendant causes confusion in the public or results in an association with the Plaintiff’ mark as the same cannot be an automatic presumption of confusion according to Section 29(3) read with Section 29 (2)(c) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

The Court relied upon the following cases, F Hoffmann- La Roche v. Geoffrey Manners & Co. Ltd. [(1970) 2 SCC 716)], Mount Mettur Pharmaceuticals Ltd v. Ortha Pharmaceutical Corporation [1974 SCC OnLine Mad 64] and CFA Institute v. Brickwork Finance Academy [2020 SCC Online Del 2744)] and opined that the rival marks are visually and phonetically dissimilar and do not cause any confusion among the public.

The Court placed reliance on the case Ruston & Hornsby Ltd. v. Zamindara Engineering Co. [(1969) 2 SCC 727] and Ramdev Food Products (P) Ltd. v. Arvindbhai Rambhai Patel [(2006) 8 SCC 726)], and held that in order to determine the likelihood of confusion, it is imperative to assess the market presence of the parties and their respective goodwill.

The Court held that the Plaintiff has not yet launched its vehicles bearing the trademark ‘EZIO’ in the market, owing to which it does not have goodwill with respect to its vehicles. On the contrary, the Defendant is a well-known player in the field of commercial electric vehicles and provided sales turnover for the financial year 2023- 2024 and promotional expenses in their reply.

The Court further held that the Defendant sells a variety of electric vehicles under a plethora of different marks in the market that uses the mark of the Defendant’ parent company ‘Mahindra/  ’ to indicate the Defendant’ connection with the Mahindra Group, that are sold only through the Defendant’ authorised dealers. Given the same, the Court opined that there cannot be any question pertaining to the Defendant seeking to piggyback upon the goodwill and reputation of the Plaintiff or cause injury thereof.

’ to indicate the Defendant’ connection with the Mahindra Group, that are sold only through the Defendant’ authorised dealers. Given the same, the Court opined that there cannot be any question pertaining to the Defendant seeking to piggyback upon the goodwill and reputation of the Plaintiff or cause injury thereof.

The Court took into account the screenshots placed on record by the Defendant to substantiate its claim that it had conducted a trademark and Google Search before adopting the marks, ‘ZEO/ eZEO’, wherein no conflicting mark including the Plaintiff’ mark ‘EZIO’ showed. Pursuant to the same, the Court opined that there is a remote possibility of the Defendant copying the mark of the Plaintiff given that the Plaintiff’ mark was disclosed on 25 September 2024, in the public domain after the Defendant had announced the launch of its vehicles. The Court also considered the Defendant’s justification of the adoption of the marks, ‘ZEO/ eZEO’ as an acronym of ‘Zero Emission Option’ to be bona fide. It was held that the present case was not where the Defendant had copied the Plaintiff’ mark in order to ride upon the latter’s goodwill and reputation.

The Court stated that both the parties in the case were engaged in the business of selling motor vehicles, i.e., high-end products. A consumer intending to purchase a motor vehicle will not make an impulsive decision unlike customers purchasing Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) at departmental stores. The customer intending to purchase a motor vehicle would visit the showroom of the car manufacturer or its authorized dealer to inspect about the car or to take test drive of the vehicle before arriving on the decision to purchase. In the current scenario, the consumers can access a plethora of information at their fingertips and perform searches to verify and authenticate the same pertaining to the products they are willing to buy.

The Court opined that Plaintiff’ vehicle is an electric passenger vehicle and on the other hand, the Defendant’ vehicle is an electric commercial vehicle, given which their shape, size and configuration and prospective customers would be different.

The Court held that the name of the manufacturer becomes very important while purchasing a motor vehicle and an average consumer considers the model of motor vehicle along its manufacturer. It is a settled position in the automobile industry that a car model is recognised by the name of the model and the manufacturer, for instance, car models such as Mercedes E220, Toyota Camry, Honda Accord, Maruti SX4 that are not recognized without the name of their manufacturer, i.e., Mercedes, Toyota, Honda, or Maruti respectively. Therefore, the name of the manufacturer is imperative for a consumer and becomes a distinguishing factor, given that the consumers consider the manufacturer’s name and not only the car model.

The Court observed that the addition of ‘MAHINDRA’ to the Defendant’ mark ‘ZEO’ makes the mark distinctive and dissimilar from the mark of the Plaintiff, both structurally and phonetically.

Conclusion

The decision of the Delhi High Court is an instructive example that reinforces the principle that a mere registration of a trademark without the actual use is not sufficient to claim exclusivity. This ruling also signifies that the house marks lead to greater exclusivity and prominence, thereby leading to minimal confusion. It also draws attention to the more general ideas of trademark law, like striking a balance between protecting consumers and acknowledging legitimate use by long-standing market participants.

[The authors are Associates in IPR practice at Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan Attorneys, New Delhi]